The Lasting Legacy of Retired Spacecraft: A Cosmic Journey

Written on

Chapter 1: Silent Sentinels of the Cosmos

A multitude of retired spacecraft, whose missions to unveil the mysteries of the universe have concluded, now drift quietly near Earth. This week, NASA plans to deactivate the Spitzer telescope, which has dedicated 16 years to cosmic observation. As it orbits the sun, it has gradually moved farther away from us.

The increasing distance, now spanning hundreds of millions of miles, has complicated the task for engineers to operate Spitzer effectively—ensuring it can recharge from the sun, relay data back to Earth, and observe the dimly lit cosmos. Consequently, the decision was made to retire it.

Once a spacecraft ceases to fulfill its purpose, it is classified as debris, regardless of its previous value. Some, like Spitzer, were placed into high-altitude orbits and may remain in space for hundreds to millions of years.

NASA's Kepler telescope, which identified thousands of exoplanets before exhausting its fuel in 2018, follows a similar path behind Earth. The European Space Agency's Herschel and Planck observatories, which halted operations in 2013, linger a million miles away at a gravitational sweet spot that keeps them in stable orbits, almost magically. The Galaxy Evolution Explorer, another NASA telescope that operated until 2012, is expected to orbit Earth for nearly 60 additional years before it disintegrates in the atmosphere. Meanwhile, Copernicus, one of NASA's earliest missions, continues to orbit Earth after ending its X-ray observations in 1981. This is just the beginning of the list.

Together, these inactive spacecraft represent more than mere space debris; they embody a legacy of years of scientific exploration launched by visionaries who could not journey there themselves. As Alice Gorman, an archaeologist specializing in space exploration, noted, "Each one tells a story about the state of knowledge at the time it was launched."

Section 1.1: The Journey of Spitzer

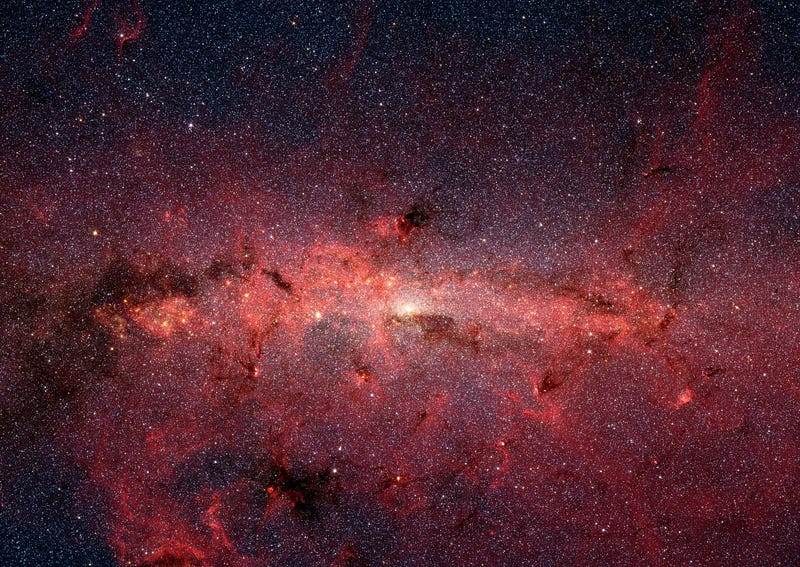

Spitzer, named after the American astrophysicist Lyman Spitzer, who advocated for space telescopes long before the first satellite was launched, was engineered to detect light in infrared wavelengths. In the 1960s, scientists experimented with infrared telescopes on balloons to bypass Earth’s atmosphere, which absorbs such radiation. NASA explains that “trying to see faint infrared sources from the ground is like trying to observe stars while the sun is up.” A National Academy of Sciences report in 1979 advocated for the deployment of infrared telescopes, stating that advancements in sensitivity had led to significant discoveries regarding nearby planets and distant stars. By the 1990s, NASA embarked on the Spitzer project.

Spitzer's ability to detect infrared light enabled it to observe very faint cosmic objects. Its findings range from our solar system to the farthest reaches of the universe. Notably, Spitzer discovered a dust ring around Saturn that was too diffuse for other telescopes to detect and captured light from galaxies billions of years old, shortly after the Big Bang. By the end of its operational life, Spitzer contributed to the field of exoplanet studies, identifying chemical elements and atmospheric patterns on distant planets orbiting other stars.

Subsection 1.1.1: The Unexpected Resurgence

While decommissioned space missions typically remain inactive, there have been exceptions. A NASA spacecraft intended to study Earth’s magnetosphere remarkably reactivated 13 years after being declared inoperative, though it never fully resumed operations. It continues to orbit Earth, nonetheless.

Section 1.2: The Future of Spacecraft

Spitzer is anticipated to linger in orbit for many years alongside its silent counterparts. As Spitzer and Earth continue their orbits around the sun, NASA predicts that Earth will catch up to Spitzer in 2051, nudging it into a closer orbit toward the sun, where it will accelerate, leaving Earth trailing behind until their next encounter.

The enduring existence of these spacecraft raises intriguing questions for Gorman. In the future, there may be numerous space archaeologists interested in the remnants left by their predecessors near and around Earth. "If a future observer were to explore the state of terrestrial science, could they deduce it from the age of the spacecraft and the nature of the instruments onboard?" Gorman muses.

Chapter 2: A Glimpse into the Future of Space Archaeology

It is certainly plausible. In some instances, future researchers might discern the functions of defunct spacecraft merely by examining them. Different instruments are required for studying various wavelengths, allowing space archaeologists to decode the significance of hardware from dusty records on Earth and correlate them with their observations of the spacecraft. For instance, the equipment designed for gamma- and X-ray detection is quite distinctive, as noted by Fiona Panther, an astronomer at the University of New South Wales in Canberra. Some spacecraft may even retain traces of samples, as suggested by Michael Busch from the SETI Institute. Future archaeologists equipped with advanced technology could approach defunct spacecraft and uncover that their instruments were intended to collect cosmic dust grains.

With sufficient research and fieldwork—at historic sites traveling through space at nearly 17,000 miles per hour—future generations could trace the evolution of space science throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Examining changes in space telescopes—the advancements in technology and the new inquiries they were designed to address—would be akin to studying the transition from the Wright brothers’ airplanes to modern commercial airliners, according to Gorman.

The first video highlights the dramatic breakup of a Russian satellite, showcasing the challenges of space debris management and its implications for future missions.

The second video, titled "Lost In Space," explores the mysteries of space exploration and the fate of the many spacecraft that have ventured beyond our atmosphere.

From this perspective, space observatories could one day serve as extraordinary museums—akin to the Smithsonian's renowned Air and Space Museum, only in the vastness of space itself. "You can visit conventional museums on Earth and witness old vehicles, planes, trains, and boats," remarked Stuart Eves, an engineer and proponent of space museums. "It would be a true loss if some of the iconic spacecraft that have greatly contributed to our understanding of the universe did not have a permanent place in history."