Understanding Regression to the Mean: Insights into Statistics

Written on

Chapter 1: The Illusion of Mediocrity in Business

In 1933, statistician Horace Secrist released a provocative book titled The Triumph of Mediocrity in Business, where he asserted that, over time, competitive market dynamics lead to a decline in the performance of top businesses while enabling poorer performers to improve. According to him, this resulted in a so-called ‘triumph’ of mediocrity. He stated,

Mediocrity tends to prevail in the conduct of competitive business. […] Such is the price which industrial (trade) freedom brings.

However, this conclusion was fundamentally flawed, and here's why.

The Misinterpretation of Data

Secrist analyzed performance metrics, including income and expenses, of numerous businesses dating back to the early 20th century. For instance, he examined 120 clothing stores from 1916, organizing them by their sales-to-expense ratios into six categories, with the top tier representing the best performers and the bottom tier the worst. His expectation was that the top performers would continue to thrive while the bottom performers would lag.

Contrary to his expectations, he observed that the rankings of top businesses tended to drop while those of poorer businesses improved in subsequent years. He attributed this trend to market competition, suggesting that companies strive to outperform their leading competitors, thereby causing those top companies to falter.

However, this reasoning is flawed. Secrist was misled by what we now refer to as the regression fallacy. What he witnessed was not merely a reaction to market forces but rather a statistical phenomenon known as regression to the mean.

What Goes Up (Must Come Down) - YouTube: This video delves into the concept of regression to the mean, illustrating how it impacts various statistical observations and outcomes in real life.

Understanding Regression to the Mean

Despite its name, regression to the mean is fundamentally a selection effect. For example, consider a group of 600 individuals rolling dice. Approximately 100 of them will likely roll a 6. If everyone rolls again, most of those who initially rolled a 6 will now likely roll a number lower than 6, simply due to probabilities. Would we attribute this change to some mysterious force diminishing their 'dice skills'? Certainly not.

Returning to Secrist’s analysis, the top businesses on his list were akin to those who rolled sixes: their success stemmed from both skill and a degree of luck. Therefore, it is not surprising if many of the top businesses experience more moderate performance in subsequent years.

The mathematician Harold Hotelling was among the first to critique Secrist's flawed conclusions, asserting that regression to the mean adequately accounts for his findings. Hotelling remarked,

“The thesis of the book, when correctly interpreted, is essentially trivial.”

Ouch. He further likened Secrist’s work to ‘proving’ mathematical principles using elephants arranged in rows, which certainly lacks rigor.

Chapter 2: The Psychology of Praise and Blame

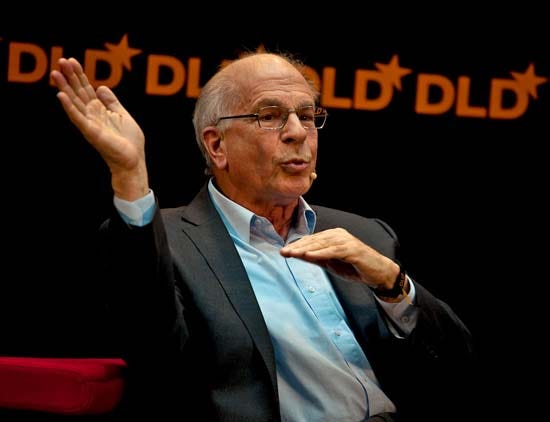

In the realm of psychology, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman recounts his experience teaching flight instructors from the Israeli Air Force that praise is typically more beneficial than blame for enhancing learning outcomes. One instructor countered this notion, arguing that cadets who received praise for outstanding performances often regressed in future evaluations, while those who were reprimanded for poor performances showed improvement. He interpreted this as evidence that blame was a more effective motivator.

Kahneman recognized that the instructor's conclusions were flawed due to overlooking regression to the mean. He articulated,

This was a joyous moment, in which I understood an important truth about the world: because we tend to reward others when they do well and punish them when they do badly, and because there is regression to the mean, it is part of the human condition that we are statistically punished for rewarding others and rewarded for punishing them.

The crux of the matter is that exceptional performances, whether positive or negative, are likely to be followed by more average outcomes. This is not just a theory; it’s a mathematical reality. Yet, humans are inclined to seek explanations for events, often creating narratives such as the instructor's belief in the efficacy of blame.

Kahneman, in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, discusses our dual cognitive systems: the fast, intuitive System 1, and the slower, analytical System 2. The narratives we construct often emerge from System 1, while recognizing regression to the mean necessitates the more reflective System 2.

TYRONE DAVIS - What Goes Up Must Come Down - YouTube: This video explores the implications of performance fluctuations and regression to the mean in various contexts.

The Scared Straight Program: A Case Study

Another illustration of the regression fallacy can be found in the Scared Straight initiative, which took juvenile offenders on tours of prisons to warn them about the harsh realities of prison life. Initially, it seemed successful, as a notable program in New Orleans reported that participants were arrested half as often after attending.

However, consider the implications of regression to the mean. By selecting a group of the most troubled youths, it was likely that their behavior would improve over time, regardless of the program.

To properly evaluate the program's effectiveness, a randomized trial was necessary. Professor James Finckenauer conducted such a study in 1978, concluding that those who attended the Scared Straight program were more likely to reoffend compared to those who did not. The results contradicted the program’s intended outcomes.

A meta-analysis by Anthony Petrosino and colleagues in 2000 reaffirmed these findings, indicating that Scared Straight did not achieve its goals. Petrosino emphasized the importance of randomized trials in assessing such programs.

Reflecting on Kahneman’s two cognitive systems, the narrative that “juveniles will change their behavior after visiting a real prison” resonates with System 1. However, it requires System 2 to rigorously analyze the data and uncover the truth, which in this case revealed the narrative to be misleading.

Conclusion: Recognizing Regression to the Mean

Certain aspects of life, such as chess, are deterministic and reflect a player's skill accurately. However, many areas involve both deterministic and random elements—business performance, academic results, arrest rates, and sports outcomes are just a few examples.

Whenever randomness is involved, regression to the mean becomes evident, potentially leading us to misinterpret outcomes if we're unaware of this effect. Exceptional performance is typically succeeded by more moderate results, but our intuitive System 1 often crafts simplistic narratives to explain these occurrences. This is the essence of the regression fallacy. It is essential to remain vigilant and engage our System 2 for deeper understanding.

References

- Jordan Ellenberg, How Not to Be Wrong: The Power of Mathematical Thinking

- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

For more of my insights, check out my profile page, including articles like:

- The Statistics of the Improbable: Exploring anomalies in data.

- How to Be Less Wrong: A Bayesian’s perspective on future predictions.