The String Theory Debate: Peter Woit's Perspective

Written on

Chapter 1: The String Theory Controversy

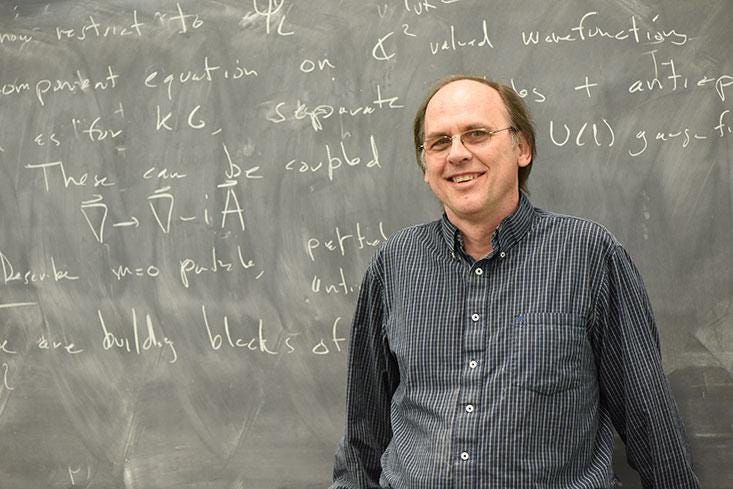

When observing Peter Woit as he teaches quantum mechanics at Columbia University—his gentle voice punctuating the equations on the blackboard—it's challenging to comprehend why a Harvard physicist once shockingly likened him to a terrorist and wished for his demise.

“I was quite concerned,” shared Woit's partner, Pamela Cruz. “I lost a lot of sleep over it.”

Woit's supposed transgression? His blog and book titled Not Even Wrong, a phrase borrowed from physicist Wolfgang Pauli, which he applies to string theory, the leading candidate for a “Theory of Everything” that seeks to unify two crucial frameworks: quantum field theory and Einstein's general relativity. Quantum field theory addresses subatomic interactions and three of the four fundamental forces, while general relativity tackles gravity, primarily relevant at grander scales. Unfortunately for physicists, these two paradigms are incompatible both logically and mathematically. String theory attempts to bridge this gap by positing that the most fundamental entities in nature are not particles, but rather strings.

Woit remains skeptical.

“This is becoming increasingly absurd; it's just ludicrous,” he recalls thinking back in 2004 when he launched his blog. “The public promotion of string theory was immense, and all the claims of its brilliance…” He shakes his head and chuckles incredulously. By 2004, after two decades of intense research, Woit felt string theory was failing to deliver.

He has been labeled an “incompetent, power-hungry … moron” and even a “stuttering crackpot-in-chief,” accused of crimes as egregious as those of Osama bin Laden.

Woit's primary criticism of string theory, both then and now, is its inability to produce testable predictions, rendering it uncheckable for inaccuracies—essentially, “not even wrong.” In contrast, general relativity allowed Einstein to make specific predictions, such as the amount of light bending around the sun. Had empirical data contradicted his predictions, general relativity would have been refuted. This criterion of falsifiability, often attributed to philosopher Karl Popper, is a hallmark of scientific rigor. Moreover, while general relativity took Einstein a decade to develop, string theory has yet to yield similar results after over 30 years.

Additionally, Woit finds the aesthetic appeal of the mathematics underpinning successful theories like Einstein’s to be lacking in string theory, which he describes as “a gory mess.” Consequently, his blog consistently critiques string theory as a “failure,” denouncing the “faddishness,” “mania,” and “arrogance” of its proponents. He has publicly urged organizations like the National Science Foundation to withdraw funding from string theory initiatives.

In his cluttered office at Columbia, where books line every wall and papers cover every surface, Woit excitedly retrieves a copy of Introduction to Stellar Atmospheres and Interiors. “There’s an almost alien yet profound comprehension of the universe that these researchers seem to tap into,” he explains. “But it should be precise, testable, and grounded in reality.”

As a high schooler in Darien, Connecticut, he became enamored with physics through stargazing using a backyard telescope, drawn to the equations that describe stellar phenomena. “I was captivated by understanding these celestial bodies,” he reminisces, reflecting on the mysterious equations that govern stellar behavior.

Woit excelled academically, with encouragement from his lawyer father and artist mother. He graduated with a bachelor's and master's in physics from Harvard and earned his doctorate at Princeton. However, during his postdoctoral research at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, he diverged from the mainstream physics path.

In 1984, he entered the field during what many now refer to as the “first string revolution,” a period marked by significant mathematical advancements that convinced numerous physicists of string theory's potential. This led to a substantial shift of researchers toward string theory projects.

Yet Woit remained immune to its allure from the outset, opting instead to explore alternative topics, which made securing a position in an already competitive field even more challenging.

“Nobody was going to hire you for mathematical physics unless it involved string theory at that time,” he says, reflecting on the futility of working on something he did not believe in. “Why stay in this field? Why not pursue something else?”

The “string wars” represent a peculiar blend of heated intellectual debates and playground-level insults.

Woit transitioned from physics to mathematics, progressing from an unpaid role at Harvard to a calculus instructor at Tufts University, and eventually becoming a senior lecturer at Columbia's mathematics department, a stable yet non-tenured role. He also manages the department's computer systems.

He expresses satisfaction with how his career has unfolded.

“Honestly, I've found mathematicians to be far more congenial than physicists,” he remarks. “Physicists are often intensely competitive.” Many of his physics colleagues aspired to emulate the likes of Murray Gell-Mann and Richard Feynman, two renowned Nobel laureates known for their sharp wit and competitive nature. “They were entertaining but not particularly pleasant people,” Woit observes. In contrast, he finds mathematicians to be more humble, acknowledging the limits of their knowledge.

Professor Henry Pinkham, chair of Columbia's math department, hired Woit in 1989 and admires him for being the “intellectual equal” of the tenured faculty while displaying no resentment toward his computer support role. He also appreciates Woit's audacity, given that several tenured faculty members in the department focus on string theory. After Woit's book release, Pinkham humorously anticipated confrontations in the faculty lounge.

While tangible altercations did not occur, the tensions were palpable. Shortly after Woit's 2006 book came out, physicist Lee Smolin published The Trouble with Physics, echoing Woit's skepticism. Together, Woit and Smolin became the most recognized critics of string theory—infamous figures, from the perspective of string theorists.

This dynamic sparked what has been dubbed the “string wars,” characterized by intense intellectual exchanges and playground-style insults in publications, panel discussions, and online forums. The professor who drew the bin Laden comparison was particularly reckless and has since departed from Harvard, yet even more level-headed individuals were irked.

“I found the books rather provoking at the time,” shares Michael Dine, a professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz and a prominent string theorist.

Others adopted a more playful perspective. “For me, it was like following a tabloid. It resembled a physics version of Big Brother or the Kardashians,” remarks Abhishek Agarwal, a physicist with experience in string theory and currently an editor for Physical Review Letters, one of the field's most esteemed journals. (Agarwal clarified that these views represent his personal opinion as a physicist, not as the editor of the journal.)

Attempting to dictate the paths physicists should pursue is misguided.

The most vehement criticism emerged in online exchanges, as expected. Woit's opponents would seize on his comments, “twisting them out of context, claiming, ‘Now I can demonstrate that Peter Woit is a fool and lacks understanding.’” He finds it astonishing that “some of the brightest minds” engage in such behavior. These disputes also permeated professional platforms. At times, Woit shared links to his blog on arXiv.org, a repository for physics papers pending peer review. However, during the height of the string wars, his posting privileges were revoked. “That situation exemplifies one of the most disgraceful and intellectually dishonest actions I have witnessed,” he states.

Curious about the interactions between Woit and Brian Greene, Columbia's most prominent string theorist, whose office is one floor above his own, one wonders about their relationship. Greene has authored popular science books and frequently appears on television. During the string wars, Greene penned an enthusiastic New York Times op-ed advocating for string theory. Presently, Woit's Columbia webpage links to Greene's article, cheekily titled “The Empire Strikes Back.”

Woit and Greene are not only divided by their academic beliefs. A 24-year-old Columbia physics major named Seth Olsen, who has studied under Woit, describes him as a remarkable educator but also “a peculiar character.” He contrasts Woit with Greene: “Talking to Brian Greene feels almost seductive; it’s as if he has a crafted persona, smooth and inviting. Woit, on the other hand, feels more genuine, like you’re peering into his soul. He often appears to be contemplating aloud, even muttering.” Some of Olsen's peers view Woit as “Brian Greene’s archnemesis.”

The string wars remain unresolved in part because even among experts, there's no consensus on the testability of string theory. String theorist Matthew Kleban from New York University argues that a sufficiently powerful particle accelerator could, in theory, demonstrate the existence of strings.

“Strings exhibit resonances,” he explains, “similar to a guitar string. Thus, there’s a distinct prediction for their behavior once we can excite those resonances. That would yield a clear and testable prediction.”

However, Dine expresses skepticism, noting that “if you ask different string theorists what string theory is, you'll receive varying responses.” Unlike Einstein’s relativity, string theory does not consist of a specific set of equations but is more of a framework or a category of equations. Regarding its testability, Dine comments, “It remains unclear what the question even means. We struggle to formulate it accurately.”

Agarwal believes that the question of testability may not be the most pertinent. He points out that a mathematical relationship identified by physicist Juan Maldacena in 1997 suggests deep mathematical ties between string theory and quantum field theory, linking it to well-established and experimentally verified physics. Known as the “AdS-CFT correspondence,” this relationship allows physicists to utilize string theory as a lens to examine more widely accepted physics. According to Agarwal, Woit “doesn’t fully acknowledge the significant insights into quantum field theories that string theory has illuminated.”

Agarwal also mentions that much of the current research in string theory is driven by the AdS-CFT correspondence rather than aspirations for a Theory of Everything. He emphasizes that the discovery of AdS-CFT illustrates the folly of attempting to dictate what areas of physics should be pursued. “You can’t orchestrate scientific progress in that manner. It’s simply impossible,” he asserts. “Imagine if funding for string theory had been cut in the mid-90s. The AdS-CFT discovery wouldn't have materialized. Based on Peter's blog, it seems he also appreciates the developments related to AdS-CFT that intersect with his interests.”

Today, the string wars have evolved into what might be termed “string skirmishes.” Woit's blog remains a popular platform among physicists and mathematicians, serving as a catalyst for ongoing discussions. His recent suspension from arXiv reignited a verbal conflict between him and prominent string theorist Joseph Polchinski from the University of California at Santa Barbara. Their exchanges escalated to accusations of “charged language,” with Woit labeling Polchinski as “sleazy and unprofessional.” Their debate continued even through the holiday season.

Nonetheless, the string wars have not disrupted the calm corridors of Columbia University. Relaxed at his desk with his hands behind his head, Woit reflects on his rapport with Greene, remarking that their interactions have always been friendly. “Brian joked that he’d share some of his increased book sales with me,” he says, flashing a crooked smile.

The first video delves into whether string theory's leading contender has been disproven, exploring the ongoing debates surrounding its validity.

The second video features discussions with Cumrun Vafa and Lex Fridman on the origins of string theory and its foundational figures.