The High Cost of Qian Xuesen's Return to China

Written on

Chapter 1: The Emotional Departure

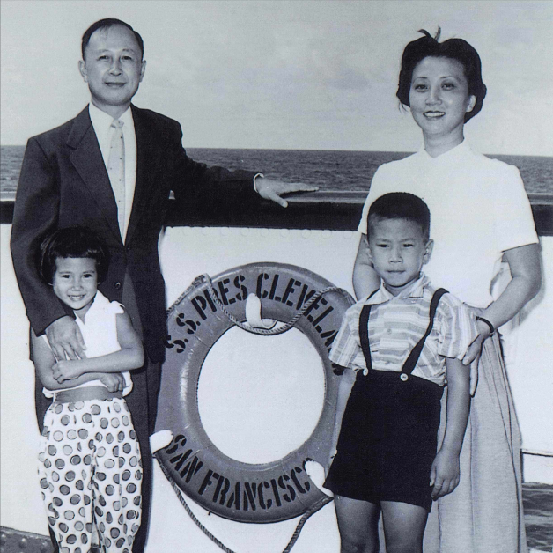

On September 17, 1955, after being under close observation by the U.S. for five years, Qian Xuesen finally set sail back to his homeland. The ship took nearly two weeks to reach its destination, and on September 30, Qian and his wife, Jiang Ying, caught their first glimpse of China on the horizon.

As they neared the shore, Qian and Jiang were overcome with emotion, tears streaming down their faces. Their young children, sensing the profound feelings of their parents, turned to their mother and asked, "Mom, where are we? When are we going home?" Jiang knelt down, gently explaining, “This is China. This is our home.”

Although Qian Xuesen was filled with emotion, he was unaware of the significant concessions China had made for his freedom. However, he grasped the magnitude of the situation from America's behavior and silently promised himself to dedicate his efforts and knowledge to his country upon his return.

What exactly did China agree to in exchange for Qian Xuesen's release?

Section 1.1: Early Life and Education

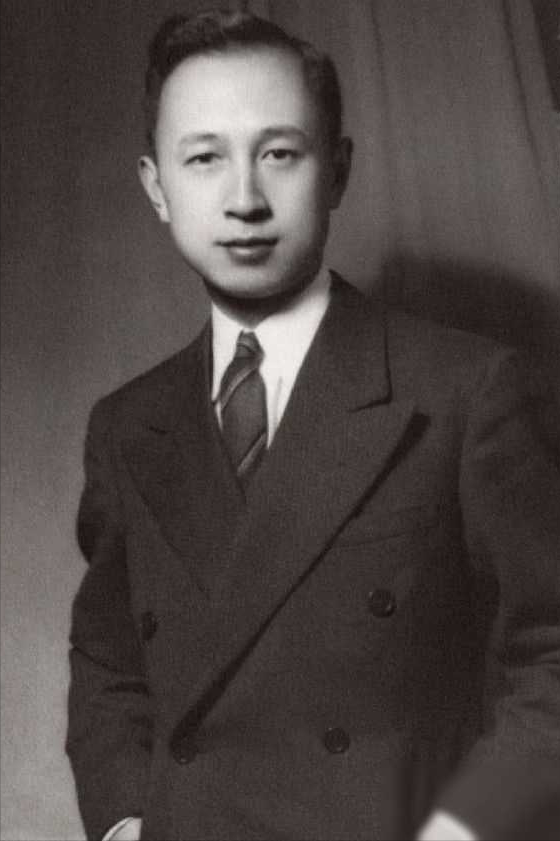

Qian Xuesen was born in 1911 into an educated family in Shanghai. From a young age, he demonstrated extraordinary intellectual abilities, quickly mastering the subjects taught by his teachers. Under the influence of his father, Qian Jiazhi, he was introduced to Western educational principles, including mathematics, physics, biology, and English, fostering a deep interest in physics.

The Qian family later relocated to Beijing, where Qian Jiazhi aimed to enroll his son in the prestigious Beijing Second Experimental Primary School, known for its innovative teaching methods. This school had a history of producing notable scholars and government officials, and the admission process was highly competitive, with only a handful of prodigies accepted from thousands of applicants.

Prospective students faced two challenging tests during the admission process. The first involved mental arithmetic, requiring children to solve complex addition and subtraction problems quickly. This was a considerable challenge for five- and six-year-olds. However, Qian Xuesen passed this test with ease. The second test assessed physical fitness, vision, and motor skills. After successfully completing these evaluations, he was accepted into the school.

In the mornings, he engaged in calligraphy, while afternoons were dedicated to scientific studies. His exceptional abilities allowed him to consistently excel and skip grades.

He later attended the Affiliated High School of Beijing Normal University and subsequently enrolled in the Shanghai School of the Ministry of Railways, now known as Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The devastation caused by the Japanese invasion ignited in him a fierce determination for China to possess its own aviation capabilities. This aspiration led him to apply for a scholarship to study aeronautics in the U.S., where he became the only foreign student in his cohort specializing in aircraft design.

For Qian Xuesen, this was an unparalleled opportunity and challenge. Recognizing his country's technological lag, he devoted himself to compressing a three-year curriculum into just one. After obtaining his master's degree, he initially chose to gain practical experience through internships before returning to China.

Unfortunately, during this period, aircraft technology was highly classified, particularly in a superpower like the U.S., which tightly controlled access to advancements. As a result, Qian Xuesen faced repeated rejections from major companies, struggling to secure employment.

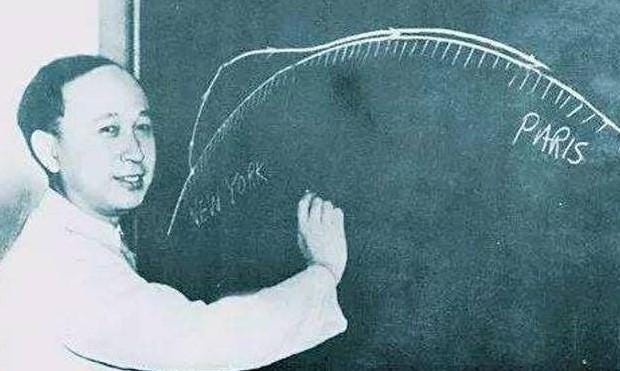

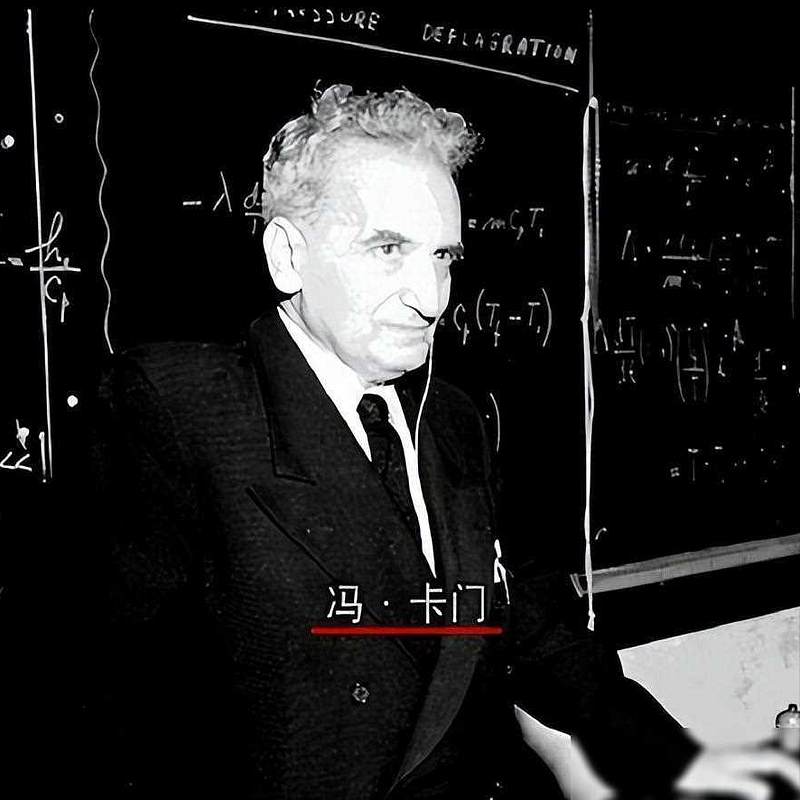

In 1936, he approached Theodore von Kármán at the California Institute of Technology, introducing himself as a Chinese student from MIT eager to study aeronautics.

Professor von Kármán, a leading scientist in aerodynamics, had established an influential aerodynamics lab at Caltech. Despite having encountered numerous students, he was intrigued by Qian Xuesen's enthusiasm and curiosity.

Von Kármán's selection process was rigorous, favoring creative thinkers over rote memorization. Many candidates were dismissed for their uninspired answers. Understanding von Kármán’s preferences, Qian discussed his vision for future technology. Impressed by the depth of Qian's explanations, von Kármán accepted him as a student.

Under von Kármán’s guidance, Qian Xuesen not only honed his aircraft knowledge but also delved into rocket science. He emerged as a rare talent in aerospace, contributing to the development of booster systems for heavy bombers and participating in numerous significant military experiments.

Chapter 2: Qian Xuesen’s Challenges in America

In 1949, upon hearing of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Qian Xuesen was eager to return and support his nation. However, the U.S. was unwilling to release such a valuable intellect. His attempts to leave were met with repeated delays.

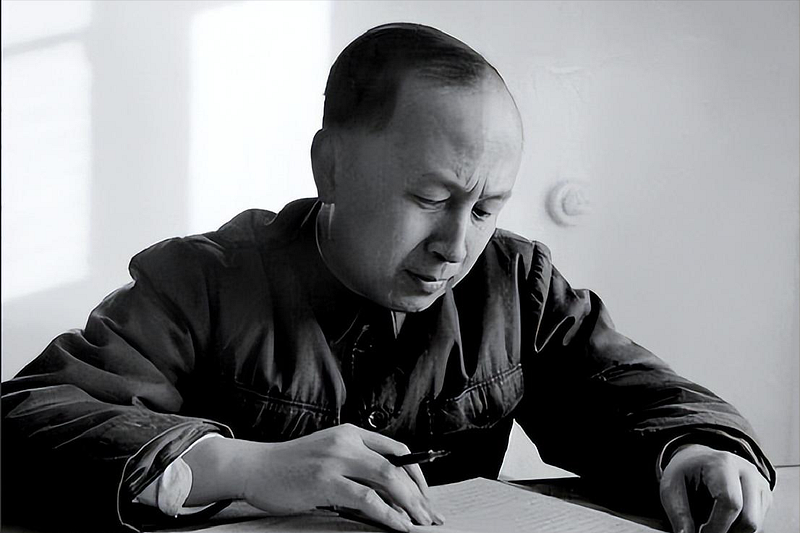

With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, suspicions arose regarding Qian Xuesen's loyalty, and he was accused of being a Chinese spy. Consequently, he was expelled from his laboratory, and U.S. authorities confiscated his passport, searched his residence, and seized critical documents.

Realizing he could no longer stay in the U.S., Qian sought to return to China, but the government thwarted his efforts, even deploying the FBI to monitor him closely. Eventually, he resigned and attempted to leave, but customs officials detained him.

During his time in detention, he endured psychological pressure, with agents checking on him every ten minutes. He was deprived of sleep, and bright lights were shone in his face during interrogations.

After two weeks, the California Institute of Technology posted a $15,000 bond for his release, but he returned home exhausted, having lost significant weight. The U.S. continued to restrict his movements, sending agents to monitor him at his residence.

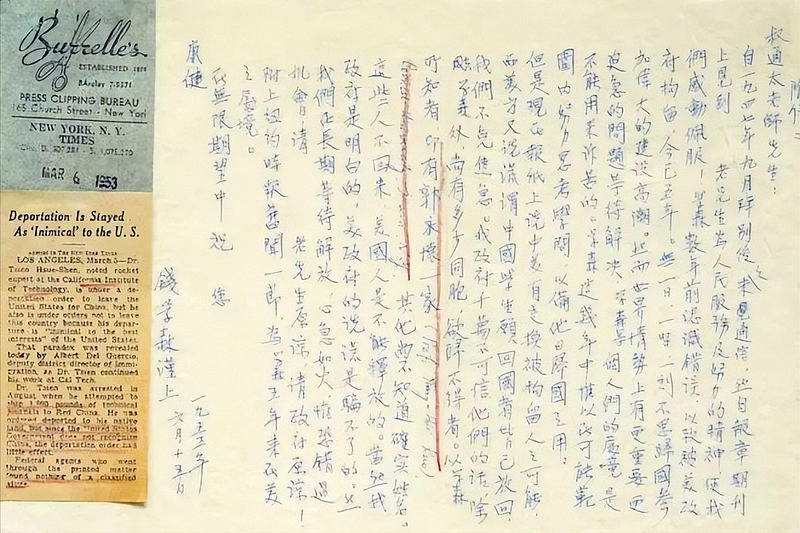

Five years later, as the FBI's scrutiny lessened, Qian Xuesen's wife, Jiang Ying, managed to send a letter detailing their struggles and his desire to return home. She discreetly mailed it to her sister in Belgium while shopping.

Jiang Hua, upon receiving the letter, recognized its importance and delivered it to Beijing, where it reached Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou Enlai. This letter served as evidence of the U.S.’s unfair treatment of Chinese students.

During the 1955 Geneva Conference, the U.S. demanded the release of 11 American pilots and spies, giving China an opportunity to request the freedom of detained Chinese scholars, particularly Qian Xuesen.

The U.S. denied any restrictions on Chinese students, claiming they chose to remain voluntarily. In response, the Chinese representative presented Qian Xuesen’s letter, reading it aloud and causing embarrassment among the American delegation.

Section 2.1: The Negotiation

The Chinese representative offered to release five pilots, insisting the U.S. must allow detained Chinese students to return home. The American side initially resisted the notion of Qian Xuesen's release.

Ultimately, a compromise was reached, where the U.S. agreed to let Qian Xuesen return after China agreed to release 11 pilots and spies. Both sides understood that Qian Xuesen's value far exceeded that of the pilots. However, the U.S. believed that the resources required to train a pilot were considerable, and they viewed Qian's five-year absence from his field as a diminishing factor.

For China, still in its nascent stages and lacking a robust air force, the release of American pilots represented a significant loss of advanced training techniques. However, the value of Qian Xuesen was deemed worth the immense cost, as he was considered worth a hundred teachers.

Finally, on September 17, 1955, Qian Xuesen boarded an American passenger ship alongside other released Chinese students, along with his family, making his long-awaited journey back to China.

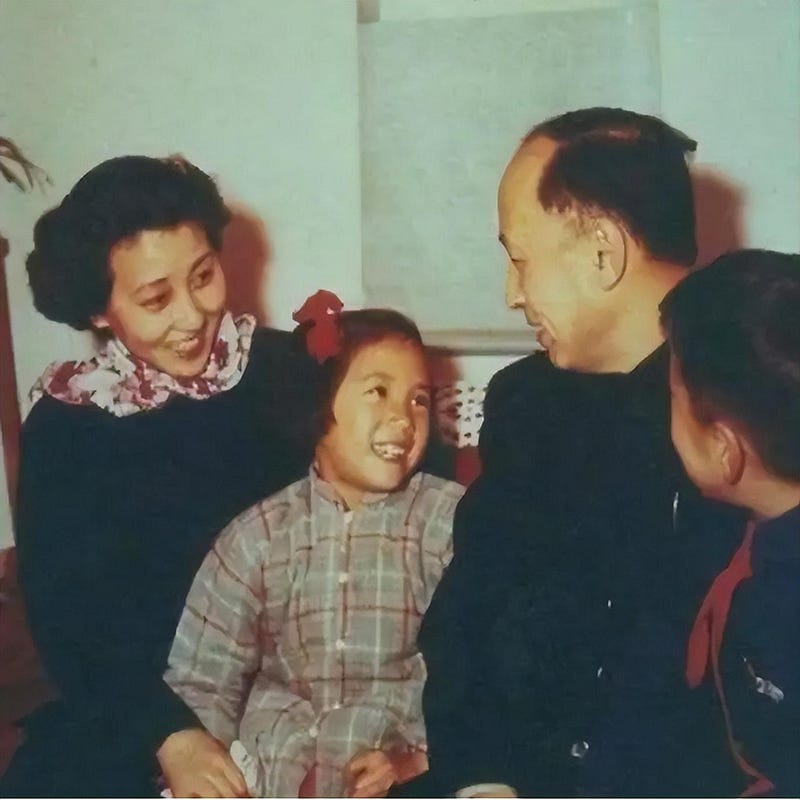

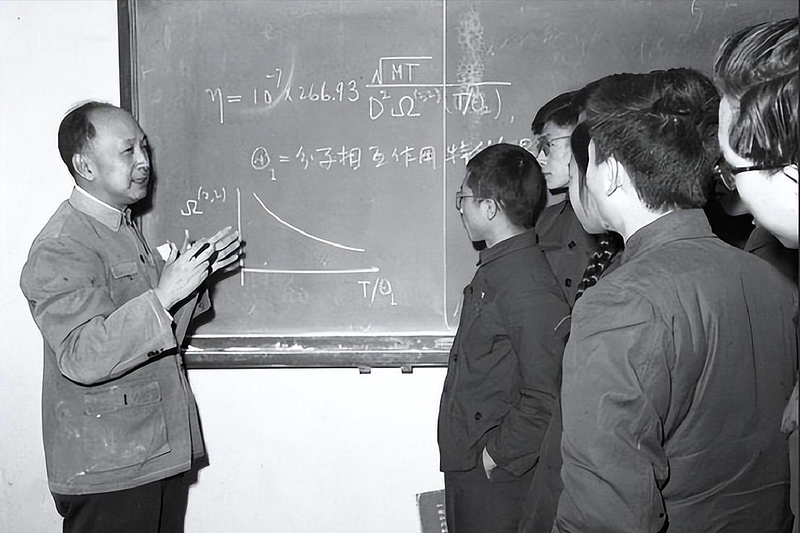

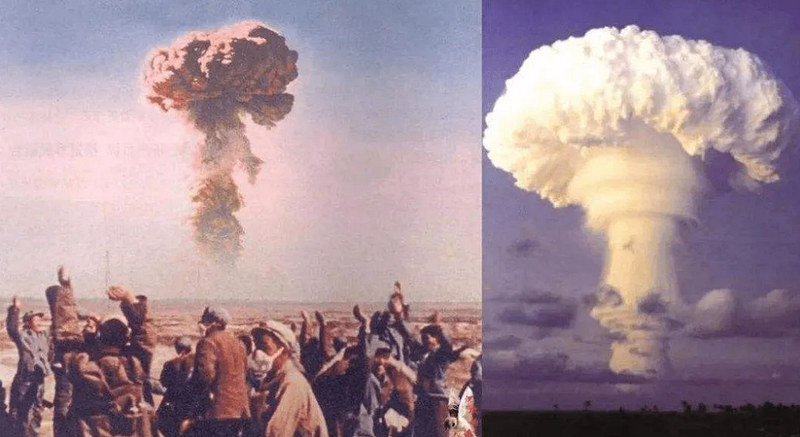

Upon his return, Qian Xuesen established a research team and commenced the education of aerospace knowledge from the ground up. Within three decades, he successfully led the development of intercontinental missiles, atomic bombs, and satellites.

In dedicating his life to strengthening China, Qian Xuesen ensured that the nation no longer lives in fear of foreign threats.