Understanding the Mysteries of Sunspots: New Insights

Written on

Chapter 1: Introduction to Sunspots

Sunspots have intrigued scientists for over 400 years. While the 11-year cycle of these phenomena is well-documented, questions about their formation have persisted. Recent research may finally provide clarity on this topic.

In the early 17th century, astronomers like Galileo were among the first to observe sunspots using rudimentary telescopes. Since then, these dark features on the Sun have been scrutinized by astronomers globally.

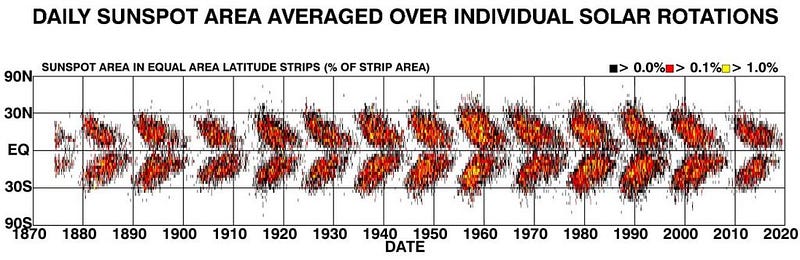

Sunspots are cooler, darker areas situated approximately 30 degrees away from the solar equator, gradually drifting closer to it as time passes. Throughout the cycle, sunspots become less frequent, reaching a minimum before the cycle restarts every 11 years. Interestingly, the magnetic orientation of these sunspots reverses with each cycle.

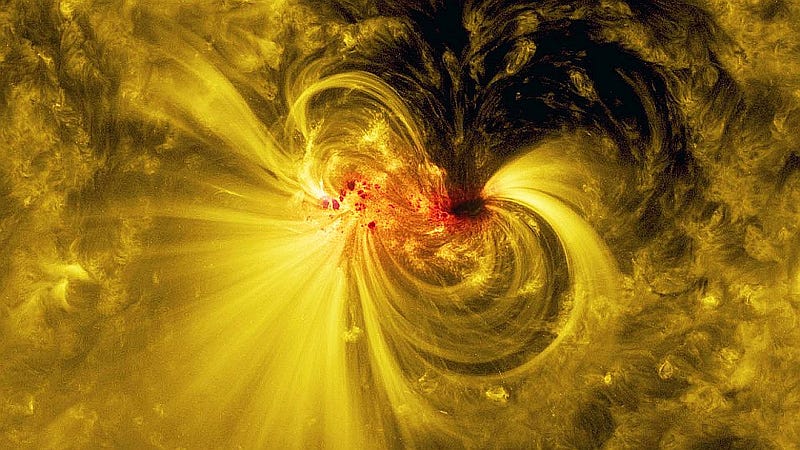

A sunspot captured by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). Image credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/SDO

Chapter 2: Unraveling the Origin of Sunspots

For centuries, the origin of sunspots and the nature of the 11-year solar cycle remained enigmatic. A novel model suggests a mechanism for their formation and may elucidate the magnetic field reversals observed in these features. This thin layer's presence could account for the behavior and appearance of sunspots, as well as other secrets of our nearest star.

“Our model differs significantly from traditional views of the sun. We believe we are among the first to unveil the nature and source of solar magnetic phenomena,” says Thomas Jarboe, a professor at the University of Washington.

Section 2.1: Characteristics of Sunspots

Sunspots appear dark due to their lower temperature compared to the Sun's photosphere. With average temperatures around 3,500 degrees Celsius (6,300 Fahrenheit), they are significantly cooler than the Sun's surface, which is about 5,500 degrees Celsius (9,900 Fahrenheit). These magnetically active regions can erupt into solar flares, releasing intense ultraviolet and X-ray radiation.

Research on nuclear fusion reactors has shown that sunspots may be explained by a thin layer of magnetic flux and plasma, teeming with free electrons, located just beneath the Sun's surface.

Sunspots emerge with little warning, indicating their formation just below the outer layers of the Sun. Traditionally, scientists believed they originated approximately 30% of the way to the Sun's core. This idea proposed that a plasma rope would rise to the surface, creating the sunspot effect.

New findings suggest that sunspots form within supergranules, located in a plasma layer just 150–450 km (100 to 300 miles) beneath the surface. The electromagnetic field in this layer is thought to destabilize, eventually shedding its outer layer into space, which leads to the formation of a new inner layer before the cycle restarts.

As these layers move at varying speeds across the Sun, they create twists in magnetic fields, known as magnetic helicity, resembling effects anticipated in fusion reactors.

The “Butterfly Diagram” depicts how sunspots appear in bands roughly 30 degrees from the solar equator at the beginning of cycles but shift closer to the equator as they progress. Image credit: Hathaway 2019/solarcyclescience.com

Section 2.2: The Influence of Solar Cycles

When circuits in both hemispheres of the Sun rotate at the same speed, a high number of sunspots are produced. Conversely, periods with fewer sunspots occur when the circuits rotate at different speeds.

“If the two hemispheres rotate at different rates, sunspots near the equator will misalign, leading to a decline in their formation,” Jarboe explains. This phenomenon may have contributed to the well-known Maunder Minimum, which lasted from 1650 to 1710.

Chapter 3: Implications of Solar Activity

Even during solar minimum, when sunspot activity is at its lowest, the Sun remains dynamic. This period allows astronomers to observe long-lasting coronal holes. These significant gaps in the Sun's corona are formed by its magnetic field and can release streams of solar particles into space at speeds reaching 2.9 million kilometers per hour (1,800,000 MPH).

The solar wind emitted from coronal holes can lead to various space weather phenomena on Earth, including geomagnetic storms, auroras, and disruptions to satellite communications and navigation systems.

“We observe these coronal holes throughout the solar cycle, but they can persist for extended periods—up to six months—during solar minimum,” explains Dean Pesnell of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Sports on a Frozen River by Aert van der Neer illustrates frozen waterways that typically do not freeze. Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chapter 4: Historical Context of Solar Activity

During the Maunder Minimum, the Sun's overall brightness decreased, leading to a drop in Earth’s temperatures and contributing to a mini-Ice Age. Although the Sun’s output was only reduced by about a quarter of a percent, this slight change had profound climatic effects, resulting in significant temperature declines.

While precise temperature readings from the late 16th century are scarce, scientists can infer conditions from ice cores, tree rings, and other data sources.

“The reduced brightness of the Sun during the Maunder Minimum caused global average surface temperature changes of only a few tenths of a degree, correlating with the minor shift in solar output. However, regional cooling across Europe and North America was 5–10 times more pronounced due to changes in atmospheric winds,” states Drew Shindell in a NASA Science Brief.

In Europe, these lowered global temperatures resulted in rivers that usually remain unfrozen, becoming solid. In North America, Native groups united to form the League of the Iroquois to combat food shortages caused by crop failures.

The first video titled "Sunspots" explores the characteristics and formation of sunspots, providing essential insights into their significance in solar physics.

The second video, "Discover Sunspots Impact on Earth's Climate & Skywatching Tips," discusses how sunspots influence Earth's climate and offers practical tips for observing them.

Chapter 5: Looking Ahead

The current solar minimum (2019–20) is not anticipated to be as severe or lengthy as the Maunder Minimum of 370 years ago. However, the magnetic fields near the Sun's poles are believed to play a crucial role in initiating solar cycles, influencing the intensity of upcoming sunspot cycles.

Weak polar fields established after the peak of Cycle 23 (2000–2002) are only half the strength of previous cycles, leading to the weakest solar cycle seen in over a century. If sunspot cycles do not stabilize soon, our planet may face a repeat of the Maunder Minimum, presenting significant challenges to contemporary society.

The findings from this new study on sunspots were published in the journal Physics of Plasmas.